About Fat and eating and drinking healthy

Fats

Fats provide energy for the body and are essential to our cells and our general function. Fats consist chemically of the glycerol esters of fatty acids (often called tri glycerides) and the fatty acids range largely in chemical structure, depending where the fat comes from. There is a lot of confusion and misinformation about which fats to eat and which to better avoid. This confusion persists today. Below, I am making an attempt to provide a holistic view. Also, a fat is generally solid at room temperature and an oil remains a liquid. The terms may be used here interchangeably.

Essential fatty acids

Our liver is able to partially synthesize fatty acids from other fatty acids that we eat, but some fat sources contain so-called ‘essential’ fatty acids: fatty acids which cannot be synthesized in our body and must be taken from what we eat. These essential fatty acids are Linolenic acid (ALA), an omega-3 fatty acid, which is found in fish, flax- and chia-seeds and walnuts for example, and Linoleic acid (LA), an omega-6 fatty acid which is also found in seeds and nuts, most vegetable oils pressed from these and some whole grains. So we have to eat these foods in order to obtain the essential fatty acids.

Saturated, mono-unsaturated, poly-unsaturated, cis and trans fats

The chemist has identified three major families of fatty acids in oils and fats: the saturated, mono-unsaturated and poly-unsaturated fatty acids. The unsaturated fatty acids are characterized by one (mono-unsaturated) or multiple (poly-unsaturated) double bonds in their molecular chain, which cannot freely rotate along the axis of the molecular chain, but which can react with oxygen (process of becoming rancid) or react with hydrogen (industrial way to harden fats). These unsaturated fatty acids are usually cis fats, which differ from trans fats by a different 3-dimensional configuration, but consist of exactly the same number and type of atoms. Double bonds are more reactive in our oxygen rich environment and can oxidize, faster at higher temperatures, in the presence of free fatty acids and in (sun) light.

Saturated fatty acids, which are found in red meats and some tropical vegetable oils such as coconut oil and palm kernel oil and in certain nuts, are the most unreactive as they have no double bond left to oxidize (that is why lamb and beef are relatively easily stored at room temperature for some time without spoiling). Most naturally occurring saturated fats are solid at room temperature.

The mono-unsaturated fatty acids are generally found in nature as mixtures in most oils and fats and in the ‘cis’ forms, and are generally considered heart healthy, although solid direct scientific proof for this is absent.

Finally, there are the poly-unsaturated fats, these are fats that are most reactive and prone to oxidation in air because they have multiple double bonds. Therefore fish should be stored on ice, to prevent the (enzymatic) oxidation of these fish oils. To this class belong the ALA (omega 3) and LA (omega 6) essential fats that our bodies need and can only take from food. Overall, the literature suggests that the cis polyunsaturated class of fats are heart healthy, but we should realize that many of the vegetable oils that contain them have only been industrially produced in the last 30-40 years. In the production process often the oils are exposed to higher temperatures, chemical extraction and treatment, steam stripping and often artificial anti-oxidants are post-added, which all help to keep the oils storage stable. The heart-healthy aspect is more indirectly derived from the fact that nuts, seeds and omega 3-oils, occurring in fish, flax seeds and walnuts, are considered healthy.

Also please note that in all naturally available food oils, whether originating from animal or plant sources, there is always a mixture of saturated, mono-unsaturated and poly-unsaturated oils present, sometimes heavily biased towards saturated oils (like in coconut oil) sometimes heavily biased towards poly-unsaturated oils, such as walnut oil or grape seed oil.

Trans fats

So called trans fats (the opposite of cis fats) are mono- and poly-unsaturated fats which are in the ‘trans’ form: these fats are either produced as a by-product by bacteria in the stomach of ruminants -and so are present in their meat and milk- or are artificially (industrially) produced to harden naturally occurring fats by partial hydrogenation of unsaturated fatty acids. The production of margarine that started at the first half of the 20th century is an example of the latter. Trans fats produced by industrial hydrogenation are considered very seriously negatively affecting our heart health, so we had better be careful not to take much. In the US these trans fats will be banned from food as of 2021. Trans fats are to be labelled on food items, but sometimes are difficult to be ‘spotted’ as in the US amounts under 0.5 g per ‘serving’ may be labelled trans fat free. Therefore, be careful when the ‘serving’ size listed on the label is small. For example, if the serving size is 14 g, the product could still contain 3% trans fats, while it is labelled as trans fat free. Watch for crackers, bread crumbs, all kind of pastry, cookies, powdered coffee creamer, ready-to-use pizza bottoms and certain deep-fry fats etc.

Red meat from ruminants and their milk do contain trans fats in small amounts (1-5% of cow milk fat is trans-fat, so 0.05-0.25% of whole milk) and so do canola (rapeseed) and soybean oil (around 0.5%), but these trans fats have a very different composition from the industrially produced trans fats. Vaccenic acid, a trans fat occurring in dairy, has been credited for anti-carcinogenic properties as mammals (such as humans) are able to convert it into rumenic acid, a conjugated linoleic acid. [S.Stender, Food and Nutrition research, Vol 52, 2008 ]

For this reason: everywhere where we read that (industrial) partially hydrogenated fats (the bad ones) have been added to food items: be warned, but trans fats from dairy are different and not considered harmful.

Fat content in animals, nuts and seeds

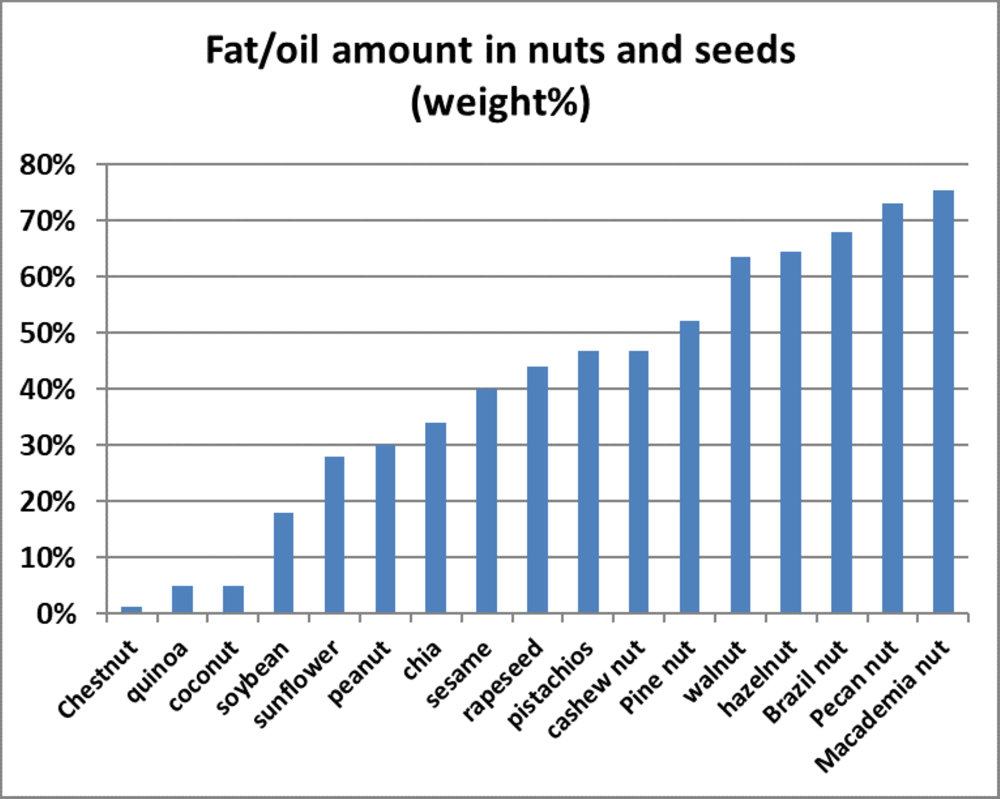

Let us first have a look at how much fat animals and plant seeds actually contain, see Figures 1 and 2, respectively. The amount of fat in animals ranges commonly from 0.1% to over 30%, also depending on what body part we look at. Fish, poultry and land animals seem to cover the same range. Some animals contain more fat than others. Domesticated animals always contain more fat than the same type of animal in the wild. In humans, athletes also have less fat than others. Most older animals also contain more fat. Seeds and nuts generally contain a higher percentage of fat, up to 75% (eg macadamia nuts).

Fat amount in animal products and in nuts and seeds (weight %)

Figure 1 and 2. Fat amount in various fish and meats (Fig 1) and fat amount in nuts and seeds (Fig 2).

Fat type in animals, nuts and seeds

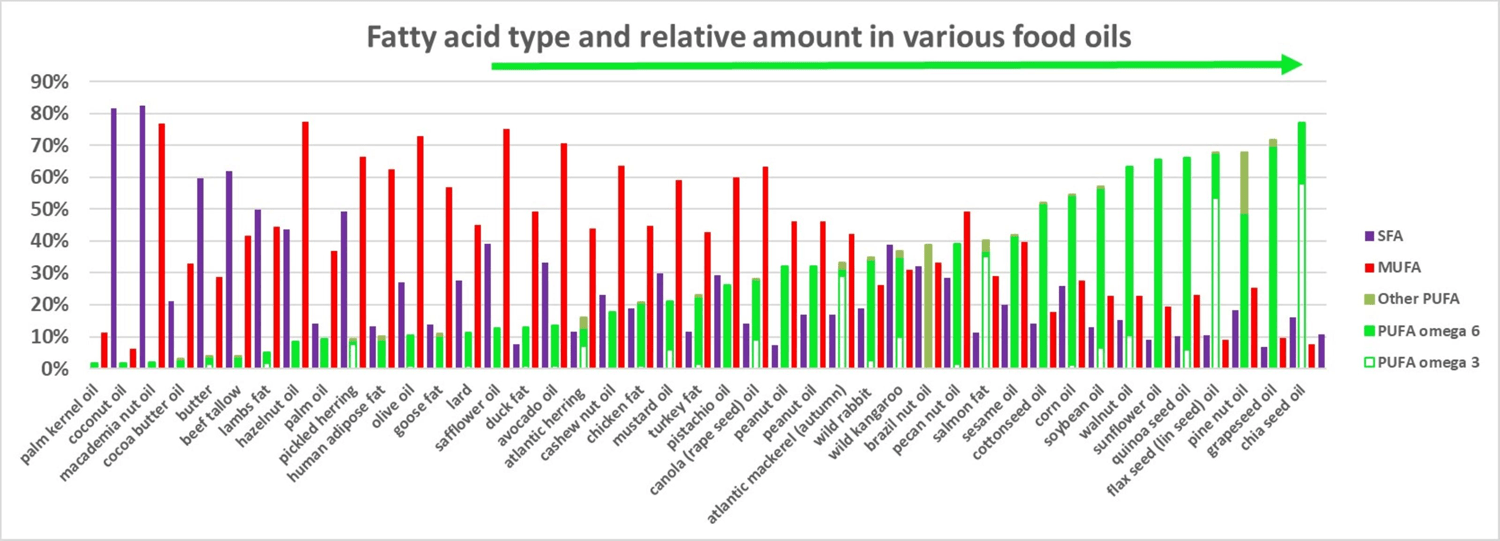

In Figure 3 the relative composition of the oils are provided in terms of saturated fatty acid, mono-unsaturated- and poly-unsaturated fatty acids, the latter are subdivided into omega-3, omega-6 oils and other poly-unsaturated oils.

Saturated fat is found in red meat, dairy products and certain tropical vegetable oils. White meat such as from fowl (chicken, goose and turkey) do have lower amounts of saturated fatty acids, while in general vegetable oils contain less saturated fatty acids, with the exception of coconut oil and palm oil, which are high in certain saturated fatty acids. Eating 100 g of fatty red meat causes more saturated fat intake than eating the same weight of very lean red meat, white meat or fish.

Fig 3. Relative fatty acid composition of fats and oils found in various foods. SFA: saturated fatty acid; MUFA: mono-unsaturated fatty acid; PUFA: poly-unsaturated fatty acid. The higher the PUFA content in the oil the more the oil is listed to the right hand side of the Figure.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]It is obvious that omega 3-oils are found in fatty fish (such as mackerel, sardines, herring and salmon), walnuts, flaxseeds, chiaseeds, soybeans, rapeseed and mustardseeds and to a lesser extent in wild rabbit, kangaroo and pecans.

A word of caution: the poly-unsaturated fatty acid containing nuts and oils are prone to oxidation which is promoted by higher temperature, by exposure to light and to air and by the presence of free fatty acid in the oils. Therefore store these in the dark at low temperature. Peeled nuts are more vulnerable than the raw, unpeeled nuts while shredded seeds (flaxseed meal) and shredded nuts have the shortest shelf life.

Also do not use oils high in polyunsaturated fatty acids for frying and baking as they easily oxidize and become rancid during the cooking process!

Flaxseeds are best shredded or ground just before use and consumption. It has been proven that taking in whole flaxseeds usually results in having the seeds end up unconsumed in our stool. Soaking them in water or yoghurt (they do form more of a gel since the outer layer of their skin dissolves) may only be of minimal help.

What oils or fats to eat: The cholesterol (blood lipids levels) debate

We have seen above which foods contain what amount and what type of fat. Now we have arrived at the most controversial of topics: how much and what oils and fats to eat and which ones to avoid?

According to the influential American Heart Association (AHA), we should eat less total fat and substitute saturated fat by poly-unsaturated fat in our diet. More recently this advice was softened in advising to replace the saturated fat by mono-unsaturated and poly-unsaturated fats [F. Sacks, Circulation (American Heart Association Journal), 15 June 2017;

From this many national health agencies are advising that we should not eat whole fat dairy -as it contains mostly saturated fats- and avoid or reduce eating red meat. We also should keep our blood cholesterol levels in check and lower the so-called ‘bad’ LDL cholesterol and try to increase the so-called ‘good’ HDL cholesterol. The AHA is referring to studies, which are currently being challenged by several scientists. While the debate seems to be fierce, sometimes requires advanced statistical knowledge and often is clouded by which organization sponsored which study, it may also indicate that we are discussing about relatively small effects (for example quitting smoking and regularly exercising, keeping your body mass index in check and preventing stress may have a much bigger positive effect on reduction of cardio vascular decease than changes in our diet), but this aside.

To bring the advice from the AHA into perspective, here follow a couple of scientific findings:

- A cohort1) study under 7447 people in Spain in the age range of 55-80 year with a high propensity to a myocardial event were given a so-called Mediterranean diet2), and were compared to a pool of randomly selected persons that followed a low fat (!) diet. They were followed a median 4.8 years and inspected for heart decease and mortality from heart decease and it yielded the following interesting results: this diet reduced the mortality related to cardio vascular decease (CVD) by 29% (as compared to the low fat diet). Please note that olive oil is rich in mono-unsaturated fats (not poly-unsaturated fats, see Fig 3) and that a Mediterranean diet is not low in fat!

- In a comparison of 11 cohort studies in which the effect of several drugs on the blood lipid (cholesterol and tri-glyceride) levels and the occurrence and mortality of CVD were studied, it appeared that only very few drugs (e.g. statins) that lowered LDL cholesterol also caused a reduction in the occurrence of CVD and related mortality. In other words a low (LDL) cholesterol level by itself, is not reducing heart decease and mortality from heart decease. [Daniel Aronov, Nov 2017].

In a subsequent paper, it was also concluded that blood LDL cholesterol levels have no relationship with mortality from heart decease. [U. Ravnskov et al. Expert Review of Clinical Pharmacology, Vol 11 (issue 10) (2018);

3. A 30 year study by Harvard medical school has shown that people who eat a handful of unsalted, unroasted (tree) nuts every day, saw a 29% reduced risk on CVD (more than Statins do) and a 11% reduced risk on cancer. [Ying Bao et al. New England Journal of medicine, Nov 21, 2013;]. Possibly it is not only for the fats, but also for the fibres and the small amounts of phytochemicals that are contained in the nut oils that are good for us.

So possibly, it depends on who you believe on how your diet should look like. Still there are a couple of similarities in the advice of the AHA, the outcome of the Mediterranean diet and the nut study: eat a handful of tree nuts daily, follow the Mediterranean diet where you can and eat whole foods (fresh fruit, whole grains and pulses with the fibres, white meats and reduce consumption of red meats and processed meats) could be a sound advice. If you enjoy a glass of wine with your food, take it! And by reducing the red meat intake you also reduce the carbon foot print.

1) a study in which at the least two groups of people, sometimes randomly picked, are followed in time, where one group is following a certain activity (e.g. a diet or not smoking) and the control group is not.

2) rich in olive oil, fruits, nuts, vegetables, a moderate intake of fish and poultry (duck, chicken, goose), a low intake of dairy products, red meats, processed meats and sweets and wine in moderation, consumed with meals for habitual drinkers [R. Estruch et al. The New England Journal of Medicine, April 4, 2013;

Vegetable oils

Most plant oils as we buy them are refined in order to keep them more storage stable and give them a higher smoke point, which renders them more suitable for frying. Also the bulk of seed oils are extracted by a volatile organic solvent from the cake, that is left after the first cold pressing, followed by solvent stripping sometimes involving steam, then a bleaching treatment followed by a filtration step over active carbon. While free fatty acids are also removed (they catalyse or promote the oxidation of the double bonds in the PUFA and MUFA), often artificial anti-oxidants such as B(utylated)H(ydroxy)T(oluene) (BHT) are added to increase storage stability. In frying oils BHT decomposes to a large degree in a short time, yielding decomposition products of unknown toxicity.

Although the addition of BHT is widely practiced, the practice is therefore somewhat questionable. And what to think of these frying oils being repeatedly re-used. Obviously deep-frying oils that consist of saturated fatty acids containing palm oil do not need protection from oxidation, and while saturated fats may be considered by some unhealthy, it would prevent the likely toxic decomposition products of BHT during the deep frying.

The cold pressed oils (the seeds or nuts are cold pressed and the first pressings contain the most flavourful oil with some other nutrients) are much more expensive than the solvent extracted oils. No wonder that healthy phytochemicals in solvent-extracted, steam-stripped, bleached oil are virtually absent. Therefore perhaps there should be more emphasis on eating raw nuts and seeds than on consuming the oils from these nuts and seeds. The exception are cold pressed and further non-treated oils such as virgin, expeller, cold pressed olive oils. These contain certain levels of healthy nutrients and antioxidants, but only the low acid containing olive oils are suitable for frying as the free acids render them unstable when heated. Also other unrefined cold pressed oils such as sunflower oil are available, but obviously are not suitable for frying as the oil would oxidize quickly to form unknown side products and get rancid.

Oils and fats for cold sauces and for frying

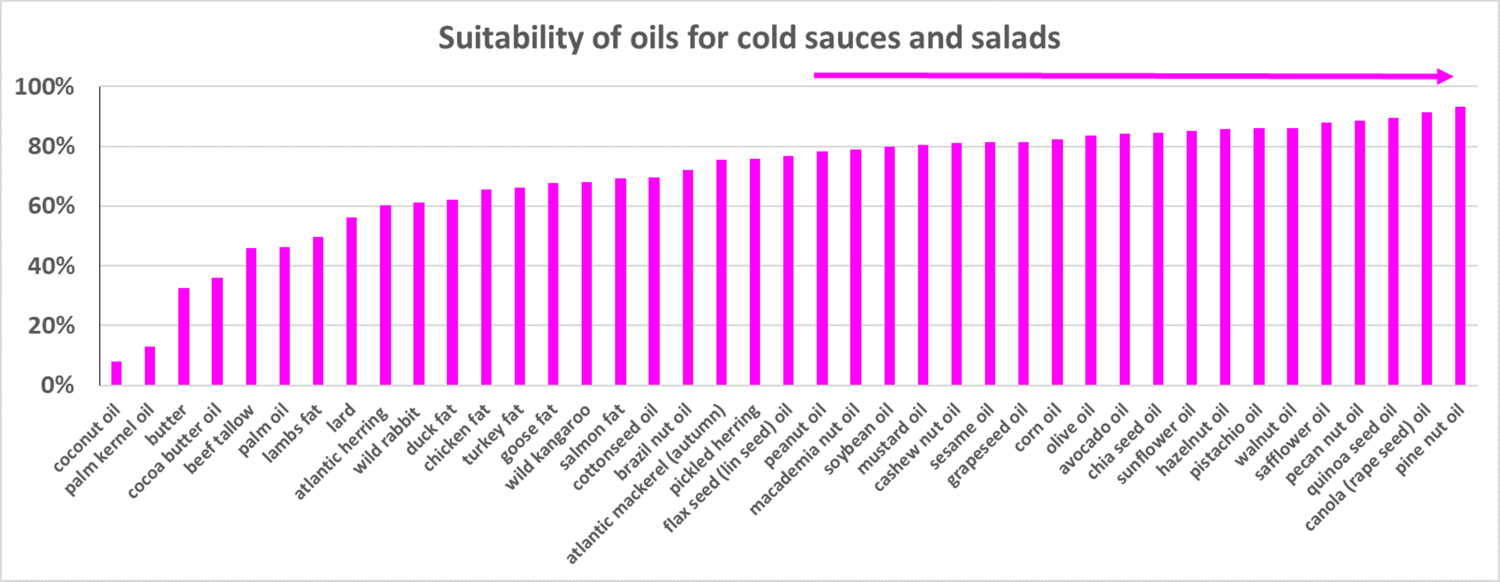

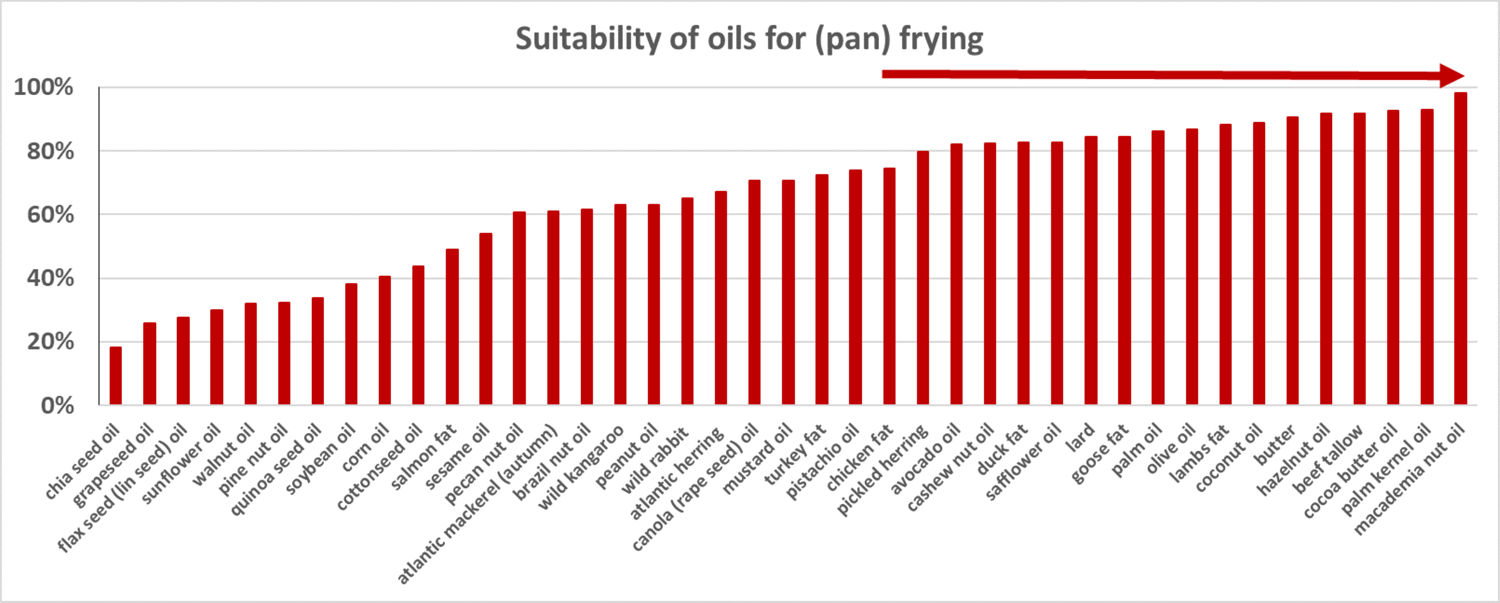

From the above we have assumed that oils high in MUFA and PUFA are more suitable for cold sauces (such as mayonaise and salad vinaigrettes) (see Fig 4). and that oils lower in PUFA are more suitable for (pan) frying (Fig 5).

Fig 4. Unrefined MUFA and PUFA containing oils are suitable to be used in salad dressings and cold sauces such as mayonnaise

Fig 5. For pan frying, oils with lower amounts of PUFA are better. Deep frying requires more stable oils with a higher smoke point: usually these are the refined oils, but also more saturated fatty acid containing oils to prevent oxidation. Do not expect much healthiness from deep fry oils.

What the chef does

It is obviously a bit confusing for the lay-person what fats to eat, as the scientists are not entirely in agreement either. I frankly have concluded from the many literature studies and further publications, that a heart healthy lifestyle includes sufficient exercise, no smoking, moderate drinking and eating a variety of foods. Let the calories be balanced by what your body burns. Prevent or reduce eating industrial trans fats and eating poly-unsaturated oils is good as long as they have not become oxidized (rancid). Also olive oil that contains a lot of mono-unsaturated fats, gets a good mark, often related to the so-called Mediterranean diet. Since most olive oil that is consumed in the Mediterranean countries is cold pressed and is rather unrefined, it provides for healthy phytochemicals as well. Keep the cold pressed virgin oils cold and store them in the dark to prevent quality deterioration.

There are large areas in Mediterranean France (and also in China) that traditionally consume a lot of duck, so I use duck fat (without any artificial additives), and olive oil to pan-fry in. Duck fat has a slightly higher proportion of saturated fatty acids than olive oil, but also a higher amount of poly-unsaturated oil and can be easily stored in the fridge (see Fig 3). I sometimes also use butter or self-refined butter fat (ghee). I use refined (BHT containing) rapeseed (Canola) oil or refined peanut oil (the smell of the peanuts is gone) mostly for deep frying, but I know the Belgians insist on frying their potato fries in beef tallow. Do not deep fry too often, but when you do: enjoy!

Cholesterol in food

Cholesterol is important for facilitating the transport of fatty acids in the blood. In common cases, over 80% of the cholesterol that is needed by our body, is made by the liver and other cells. Less than 20% comes from food. In recent years, the opinion on dietary cholesterol intake has somewhat changed. For quite some time eggs were out and consumption of shell fish and shrimp frowned upon. That has changed as it appeared that so-called good HDL blood cholesterol levels were influenced by saturated fat (negative effect) and fibre intake (positive effect) but hardly by the cholesterol from the food that we eat. Even the AHA let us now eat eggs again in moderation! [G. Soliman in Nutrients, (2018) Jun (10 (6) 780. So eat shrimp and shell fish, take eggs and some organ meat now and then is fine too. That debate also in this area continues is reflected by a recent study that suggested that eating eggs (and thereby dietary cholesterol) is directly linked to the occurrence of cardiovascular decease (CVD) and mortality from CVD. [V. Zhong et al., Journal of the American Medical Association 2019; 321 (11), 1081.]